Components

Earthquake risk is made up of four components: earthquake hazard, local subsoil, building vulnerability, and people and assets affected. To determine the earthquake risk, these four components must be combined.

Earthquake hazard

Earthquake hazard indicates how often earthquakes might occur in a given location and how strong the shaking is likely to be. It is based on knowledge of tectonics and geology, information about the history of earthquakes, and wave propagation models.

In Switzerland, the canton of Valais is the region with the highest hazard, followed by Basel, Grisons, the St. Gallen Rhine Valley, Central Switzerland and then the rest of the country.

Earthquake-resistant residential and commercial buildings in Switzerland are designed to withstand shaking that can be expected to occur around once every 500 years. The lifetime of a building is approximately 50 years. The probability of any residential or commercial building experiencing such an earthquake within this 50-year period is therefore 10%.

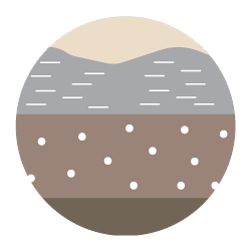

Local subsoil

The local subsoil influences how strong the tremors of an earthquake will be at a particular location: the softer the subsoil, the more the seismic waves are amplified and the greater the likelihood of damage. In places with soft sediments, such as in valleys and on lake shores, as well as in parts of the Swiss Plateau, earthquake-triggered shaking can be up to ten times stronger than somewhere located on solid rock.

Building vulnerability

Vulnerability describes the susceptibility to damage of buildings at given earthquake magnitudes. For the earthquake risk model, the vulnerability for different, representative building types was derived based on their characteristics and divided into so-called vulnerability classes. On this basis, the building stock was statistically assigned to these classes based on simple characteristics such as the number of storeys or the construction period. This, combined with information on the people and assets affected, makes it possible to determine the consequences for residents and the financial losses. The latter are expressed as a proportion of the building reinstatement costs. The majority of Swiss buildings were not built in accordance with the currently applicable building standards for earthquake-resistant construction.

Classifying the vulnerability of existing buildings according to construction materials is not helpful. For each type of construction, good and bad examples of earthquake behaviour can be found. The design of the supporting structure is the primary factor determining a building's vulnerability. For example, a building with continuous bracing walls running from the roof to the foundation without interruption has a much lower vulnerability than a similar building where the bracing walls are interrupted at ground-floor level and replaced by columns. This classic weak point, known as the 'soft storey', is an indication of very inadequate earthquake resistance. Older masonry buildings with timber beam ceilings can also be particularly vulnerable if the masonry is of poor quality and the façades are not sufficiently connected to the ceilings and transverse walls.

Affected people and assets

An earthquake risk only exists where there are people and assets. This component therefore encompasses the spatial distribution of Switzerland's more than 2 million residential, commercial and industrial buildings. It also factors in the number of people occupying these buildings and the replacement costs.

In general, densely populated, heavily built-up areas such as cities and agglomerations have a higher exposure concentration than rural regions and are therefore exposed to a higher earthquake risk. The possible impacts of earthquakes on infrastructure and the variations in building occupancy over time are not yet represented in the earthquake risk model.